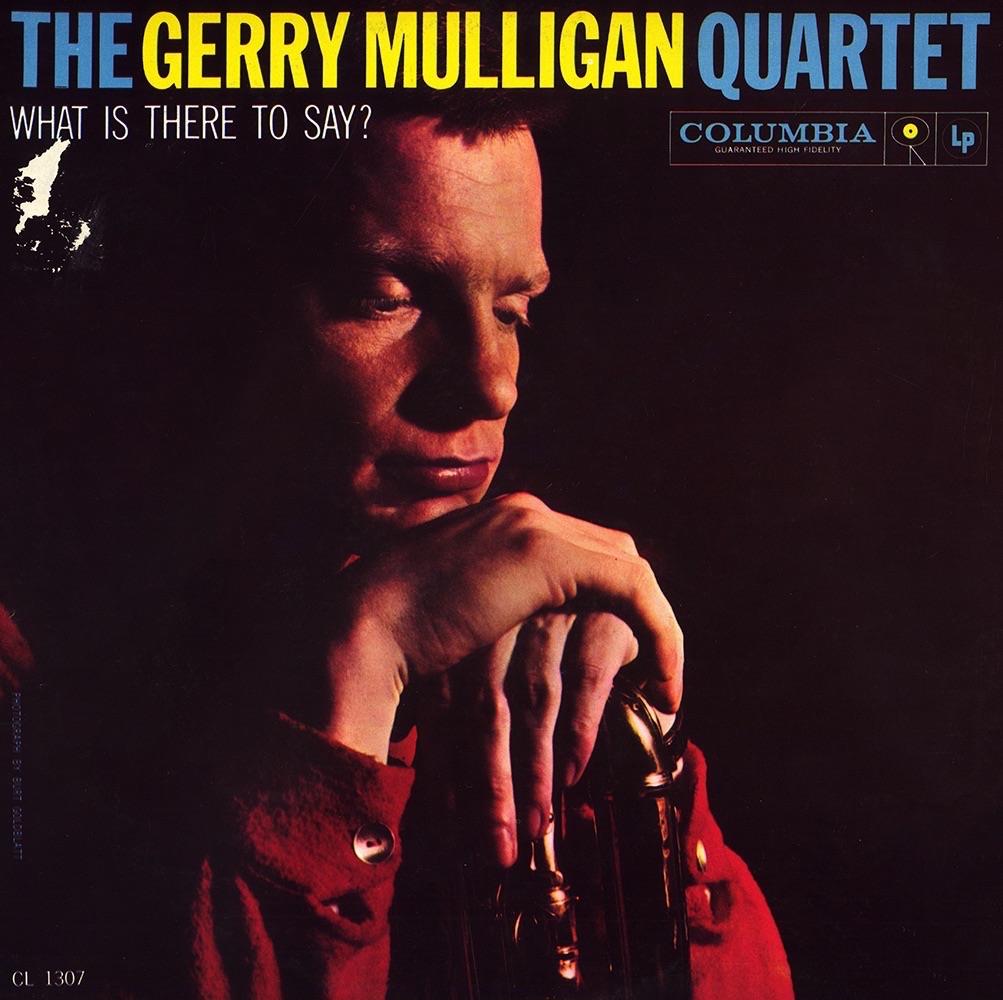

I have an original 1959 mono pressing of this record on the classic "6-eye" Columbia label. Mine's a Canadian pressing, meaning it is a maroon label with silver eyes (American pressings have red labels with black eyes). The 1959 "6-eye" pressings are the most sought after, not that they command a lot of money. You'll pay about $20 for it - if you can find one!

That's the hard part. Those old "6-eyes" get gobbled up almost as quick as they appear, and when you do find one it is usually in pretty rough shape. The cover on my copy has a peel-tear where I'm guessing someone tried to pull off a sticker that maybe detailed the nice condition of the cover - because it's otherwise fine. The record itself looked kind of scruffy at first glance, but I bought it anyway and brought it home because all the record store wanted for it was three bucks.

So I didn't really care what condition it was in. For not even the cost of half a Starbucks double espresso I was willing to gamble. I might have lucked into a hard-to-find and nice sounding original pressing by one of my favourite jazzmen. It seemed a reasonable risk.

When I got home I cleaned the record on my VPI 16.5 and plopped it onto the turntable. It was playable but scratchy, enough so as to justify the cheap price. Oh, well.

But then a couple of years later I bought an iSonic ultrasonic record cleaner (it's probably more accurately called a record restorer) and decided to put this record through the restoration process. The result was, in a word, incredible! The record emerged from its ultrasonic swim absolutely quiet - pristinely so - and sounding more musical than I ever imagined it could. The iSonic returned the record to as close to its original, mint condition as is possible - which in this case is a very strong VG+.

And that's a beautiful thing because this recording - this pressing of this recording - is known for its musicality and spaciousness.

What Is There To Say? is considered one of Mulligan's finest albums, which is quite a designation if you think about how many great LPs he released. It is a piano-less quartet he leads here that includes Art Farmer, on trumpet. The interplay between these two jazz icons is sophisticated yet at times playful. Mulligan has headed sextets, trios, concert bands … he's done just about everything one can do in jazz, and some things he's done at breakneck speeds. But here he slows things down. Here he's understated, and this is the kind of stuff I like to listen to most.

The record opens with two familiar standards, which were probably chosen for their commercial potential. The title tune, written by Yip Harburg (who also composed Over The Rainbow) and Vernon Duke, would have been familiar to most people at the time of the album's release, which more than likely helped pad the bottom line. Just in Time, which follows, is well known to almost everyone.

Mulligan's News From Blueport is up next and is followed by Festive Minor, probably the album's "coolest" number. As Catch Can is the liveliest song of the bunch, and a gorgeous rendition of My Funny Valentine follows. The quartet then plays another uptempo piece called Blueport before winding things down with Utter Chaos, which is not in any way chaotic.

This LP was most likely recorded at Columbia's 30th Street Studios, which was legendary for its ability to impart a sense of spaciousness to the records that were recorded there, which is very much evident on What Is There To Say? I don't know what it is about some rooms, but that studio was certainly exceptional in this regard. I have a friend who recorded in it and he confirms this (although he preferred Sunset Sound Recorders, which he said was even better).

What Is There To Say? is such an easy LP to listen to. Mulligan's sound pretty much defined the so-called cool jazz genre that was the all rage back then, and this record easily fits into that genre, particularly the title track, where Mulligan seems to float all over the place effortlessly. It's just plain gorgeous, and the copy I have has somehow survived 63 years with that gorgeousness intact and free of the wear and tear most similarly-aged records accumulate over time.

Mulligan wrote the liner notes. In them, he complained that too much music criticism can ruin the jazz music listening experience. He wrote that, " … some of the people who do the most talking about jazz (that may even be the basic problem, right there!) don't seem to get any real fun out of listening to it. It seems to me that all the super-intellectualizing on the technics of jazz and the lack of response to the emotion and meaning of jazz is spoiling the fun for listeners and players alike."

It's true if you think about it, and it's also true that a lot of audiophiles - people like me who collect music and don't mind spending a considerable sum on a record restoration machine - tend to listen to their equipment instead of the music. The inherent sonics of a properly recorded/mastered/pressed analogue LP will make any decent stereo system sound its best, and it's easy to fall into that audiophile equipment-listening trap where one marvels at how good the speakers sound or how much of a difference that really expensive cable makes. Don't get caught up in that. Buy the best stereo you can afford and then sit back and listen to the music.

Critics and audiophiles are probably the worst two things to ever happen to recorded music. Does the music move you? Does it say something to you? This record certainly resonates with me. It's also a pure analogue recording that was made with considerable care. That's largely why I am able to - 63 years and an entire generation after the fact - still marvel at its beauty.

The CD won't do that. Streaming music won't do that. But this old slab of wax does.

What Is There To Say? has been reissued several times, including a 2-LP, 45-RPM version on Analogue Productions that, some reviewers have said, sounds almost as good as this pressing.

If you see this little gem hiding in the crates the next time you're able to dig through them - your first "post-pandemic" dig, maybe - scoop it up. Don't worry too much about the condition. Instead, go visit that friend who owns an ultrasonic cleaner. Take a nice bottle of wine with you. And maybe a couple of cigars.

I have an original 1959 mono pressing of this record on the classic "6-eye" Columbia label. Mine's a Canadian pressing, meaning it is a maroon label with silver eyes (American pressings have red labels with black eyes). The 1959 "6-eye" pressings are the most sought after, not that they command a lot of money. You'll pay about $20 for it - if you can find one!

That's the hard part. Those old "6-eyes" get gobbled up almost as quick as they appear, and when you do find one it is usually in pretty rough shape. The cover on my copy has a peel-tear where I'm guessing someone tried to pull off a sticker that maybe detailed the nice condition of the cover - because it's otherwise fine. The record itself looked kind of scruffy at first glance, but I bought it anyway and brought it home because all the record store wanted for it was three bucks.

So I didn't really care what condition it was in. For not even the cost of half a Starbucks double espresso I was willing to gamble. I might have lucked into a hard-to-find and nice sounding original pressing by one of my favourite jazzmen. It seemed a reasonable risk.

When I got home I cleaned the record on my VPI 16.5 and plopped it onto the turntable. It was playable but scratchy, enough so as to justify the cheap price. Oh, well.

But then a couple of years later I bought an iSonic ultrasonic record cleaner (it's probably more accurately called a record restorer) and decided to put this record through the restoration process. The result was, in a word, incredible! The record emerged from its ultrasonic swim absolutely quiet - pristinely so - and sounding more musical than I ever imagined it could. The iSonic returned the record to as close to its original, mint condition as is possible - which in this case is a very strong VG+.

And that's a beautiful thing because this recording - this pressing of this recording - is known for its musicality and spaciousness.

What Is There To Say? is considered one of Mulligan's finest albums, which is quite a designation if you think about how many great LPs he released. It is a piano-less quartet he leads here that includes Art Farmer, on trumpet. The interplay between these two jazz icons is sophisticated yet at times playful. Mulligan has headed sextets, trios, concert bands … he's done just about everything one can do in jazz, and some things he's done at breakneck speeds. But here he slows things down. Here he's understated, and this is the kind of stuff I like to listen to most.

The record opens with two familiar standards, which were probably chosen for their commercial potential. The title tune, written by Yip Harburg (who also composed Over The Rainbow) and Vernon Duke, would have been familiar to most people at the time of the album's release, which more than likely helped pad the bottom line. Just in Time, which follows, is well known to almost everyone.

Mulligan's News From Blueport is up next and is followed by Festive Minor, probably the album's "coolest" number. As Catch Can is the liveliest song of the bunch, and a gorgeous rendition of My Funny Valentine follows. The quartet then plays another uptempo piece called Blueport before winding things down with Utter Chaos, which is not in any way chaotic.

This LP was most likely recorded at Columbia's 30th Street Studios, which was legendary for its ability to impart a sense of spaciousness to the records that were recorded there, which is very much evident on What Is There To Say? I don't know what it is about some rooms, but that studio was certainly exceptional in this regard. I have a friend who recorded in it and he confirms this (although he preferred Sunset Sound Recorders, which he said was even better).

What Is There To Say? is such an easy LP to listen to. Mulligan's sound pretty much defined the so-called cool jazz genre that was the all rage back then, and this record easily fits into that genre, particularly the title track, where Mulligan seems to float all over the place effortlessly. It's just plain gorgeous, and the copy I have has somehow survived 63 years with that gorgeousness intact and free of the wear and tear most similarly-aged records accumulate over time.

Mulligan wrote the liner notes. In them, he complained that too much music criticism can ruin the jazz music listening experience. He wrote that, " … some of the people who do the most talking about jazz (that may even be the basic problem, right there!) don't seem to get any real fun out of listening to it. It seems to me that all the super-intellectualizing on the technics of jazz and the lack of response to the emotion and meaning of jazz is spoiling the fun for listeners and players alike."

It's true if you think about it, and it's also true that a lot of audiophiles - people like me who collect music and don't mind spending a considerable sum on a record restoration machine - tend to listen to their equipment instead of the music. The inherent sonics of a properly recorded/mastered/pressed analogue LP will make any decent stereo system sound its best, and it's easy to fall into that audiophile equipment-listening trap where one marvels at how good the speakers sound or how much of a difference that really expensive cable makes. Don't get caught up in that. Buy the best stereo you can afford and then sit back and listen to the music.

Critics and audiophiles are probably the worst two things to ever happen to recorded music. Does the music move you? Does it say something to you? This record certainly resonates with me. It's also a pure analogue recording that was made with considerable care. That's largely why I am able to - 63 years and an entire generation after the fact - still marvel at its beauty.

The CD won't do that. Streaming music won't do that. But this old slab of wax does.

What Is There To Say? has been reissued several times, including a 2-LP, 45-RPM version on Analogue Productions that, some reviewers have said, sounds almost as good as this pressing.

If you see this little gem hiding in the crates the next time you're able to dig through them - your first "post-pandemic" dig, maybe - scoop it up. Don't worry too much about the condition. Instead, go visit that friend who owns an ultrasonic cleaner. Take a nice bottle of wine with you. And maybe a couple of cigars.