Super Session is an album from 1968 by Al Kooper that also features guitarists Mike Bloomfield and Stephen Stills, although Bloomfield and Stills do not play together on the album. Side one contains tracks featuring Kooper and Bloomfield and side two Kooper and Stills. The record peaked at number 12 on the Billboard 200, and has been certified a gold record by the RIAA.

Kooper and Bloomfield had worked together previously on Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited and backed him at his controversial appearance at the Newport Folk Festival in July, 1965. Kooper had recently left Blood, Sweat & Tears - a band he formed - after their debut album was recorded and became an A&R man for Columbia Records. Bloomfield was a member of Electric Flag (which also featured keyboardist Barry Goldberg, drummer Buddy Miles and bassist Harvey Brooks), but that group was imploding. Kooper invited Bloomfield to a studio jam session, and when Bloomfield agreed Kooper booked two days of studio time and recruited Electric Flag members Goldberg and Brooks to sit in.

On the first day, the quintet recorded a group of mostly blues-based instrumental tracks, including His Holy Modal Majesty, a tribute to the late John Coltrane. On the second day, Bloomfield failed to show up. That's when Kooper called Stephen Stills, who was then in the process of leaving Buffalo Springfield, to fill in. With Stills now playing guitar, the musicians cut several mostly vocal tracks, including It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry (from Highway 61) and a lengthy and atmospheric take of the Donovan song, Season of the Witch.

The resulting record - this one - cost just $13,000 to make and went gold upon release. It's success opened the door for so-called "supergroups" (Blind Faith, Crosby, Stills & Nash, etc). Kooper eventually forgave Bloomfield for his disappearing act and the two later played in concert together on several occasions, which resulted in the album The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper, a sort of Super Session follow-up.

The copy I am listening to is the Mobile Fidelity reissue, released in 1983, which sounds exceptional. A nice punchy low end, full midrange and highs that aren't too bright. The vinyl is a little noisy, but that's probably because it's a previously owned record. It's not terribly noisy, it's just not as quiet as most of the other records in my collection. Over all it sounds great. It is somewhat hard to come by but can still be found in decent shape for about $100. I've seen a few here and there priced even less, and several priced quite a bit more.

Aside from the stereo version, a 4-channel quadraphonic version was also released, although I never understood why. I never got into the whole quad thing when it happened, which was a fore-runner of today's 5:1 or 7:1 surround sound.

A limited edition hybrid SACD by Audio Fidelity was also released in September 2014.

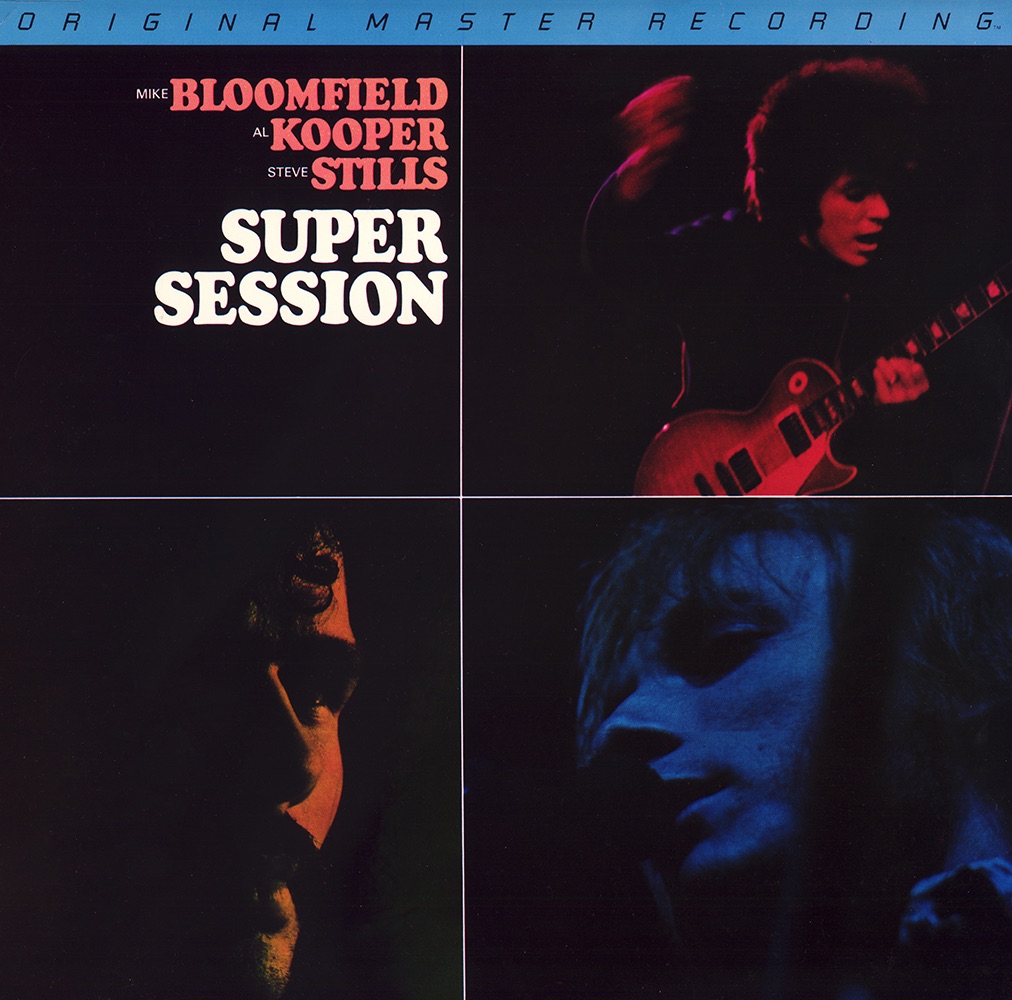

Session photos

The really interesting and odd thing about Super Session is it's success. Kooper said in an interview with Bloomfield Notes several years ago, “That was the last thing on our minds, that it was going to be a successful record. I was trying to emulate the Blue Note jazz records of the ’50s in concept, put a bunch of guys that can really play in a room and let ’em jam. Make rock ’n’ roll more of an art form, comparing it to those jazz records. And it turned out to be the most successful record of our careers.”

The timing was, in a word, perfect. All three key players were at career forks in the road. But it was probably, on some cosmic level, always meant to happen. Kooper and Bloomfield, having met at Bob Dylan's Like A Rolling Stone studio session in 1965, hit it off when Kooper saw what Bloomfield could do with his guitar. When keyboardist Paul Griffin moved from the Hammond B-3 organ to the piano, Kooper - who'd never played a B-3 before - began improvising on it. Dylan liked what he heard and told him to continue playing. As Kooper later told it, “there is no music to read. The song is over five minutes long. The band is so loud that I can’t even hear the organ, and I’m not familiar with the instrument to begin with. But the tape is going, and that is Bob fucking Dylan over there singing, so this had better be me sitting here playing something.”

Kooper’s keyboard and Bloomfield’s guitar became the song's unlikely signature sound, and Dylan was so impressed he invited both men back to the studio for the sessions that would result in Highway 61 Revisited.

In 1966, when Bloomfield was riding high with the Butterfield Blues Band and their iconic East-West album, Kooper was experiencing similar success with the Blues Project. But by 1967 they had both left those bands. Kooper went solo and Bloomfield formed Electric Flag. A few months after the Monterrey Pop Festival, where both musicians appeared separately, Kooper formed Blood, Sweat and Tears and began work on their debut album. But by the following spring both Kooper and Bloomfield were again out of work and that’s when Kooper - who’d begun serving as an A&R man for the Columbia Records (who had signed him as a solo act) - got the idea for this record and called Bloomfield.

“It was really a fated thing,” Kooper told writer Jeff Tamarkin in an interview in the 1990s. “We had so much in common that we had to do something together. So many similarities. We had both played on the Dylan sessions and we were friends through the Butterfield and Flag period. We were both approximately the same age, we were both Jewish, we both loved blues, we both were in blues bands that we left to form horn bands. We were both thrown out of the horn bands that we formed and then there we were. There was a real genuine affection for each other. So when I started working as an A&R man at CBS, I called him and said, ‘Let’s make a jam session album,’ and he was into it.”

But after one day in the studio Bloomfield, who suffered from insomnia, disappeared. “Bloomfield split in the middle of the night,” Kooper told Tamarkin. “He left a note that said, ‘Couldn’t sleep, bye.’ So I called every guitar player I knew in Los Angeles and San Francisco - Jerry Garcia, Randy California, Steve Stills and I don’t even remember who else. Stills was the one who got it together.” They worked blind, as nobody had any new material on offer. Also, Kooper was worried about getting the rights for Bloomfield - who was then signed to Atlantic Records - to appear on a recording for another label, a not so insignificant detail that needed to be worked out. But the way it happened is how Atlantic ended up with Graham Nash - who was at the time signed to Epic with the Hollies - to round out their new group, which at that moment in time consisted of David Crosby and Stephen Stills. The labels simply swapped Stills for Super Session and Nash for what would become Crosby, Stills & Nash.

Talk about fate. Only at that moment in time, and what if it hadn't worked out?

Super Session was and still is a groundbreaking record, the first real rock jam session to get an official release. It was an unplanned magical moment, the kind of creation that will likely never happen again in this modern world of pre-packaged, committee-made music. Kooper is now more-or-less retired at 76, and among his many achievements over the ensuing years was his discovery and nurturing of a fledgling Florida band called Lynyrd Skynyrd.

Bloomfield died in 1981 under mysterious circumstances at age 37.

UPDATE:

I have now acquired the Speakers' Corner edition of this record. The hype sticker on the front cover proclaims that "this LP is an entirely analogue production!" and because there's an exclamation mark at the end of it I'm willing to gamble and take their word for it.

But it's not much of a gamble. Speakers' Corner is a label I have come to trust. I have many of their releases in my collection and every one of them sounds excellent. They are a dedicated bunch of music lovers and this record was pressed at Pallas, In Germany, who are renowned for quality pressings.

This pressing sounds wonderful! The stereo separation is obvious, maybe a little more pronounced than on the MoFi pressing (but not much), and the centre sweet spot is right where it should be. Of course, this being a brand new Speakers' Corner pressing means it's a very quiet record - a bit quieter than my second hand MoFi - and it's obviously an analogue production. That is something I really do hear, and it's missing on every one of the digital versions of this recording I've heard. Spaciousness and warmth - the two hallowed ghosts of analogue. Some believe, some don't. But on a half decent rig it is very much audible.

So. Which pressing is the better one? At this level it just doesn't matter. When I listen to either one I am delighted by how spectacular they both sound. There's nothing wrong with either one, although I suppose there may be some slight differences. Is the MoFi a bit muddier? Maybe, but so what? It still sounds fucking great. We're talking pure analogue here, so it's hard to find fault, and any faults could be related to your turntable, speakers, amp, cables or even the electrical system in your home. Or maybe it's your ears. So just listen to the music and enjoy it.

I think I'll probably trade the MoFi and use the equity to get some more really good records into the collection!

This is one of my all-time favourite recordings - either pressing will do - and I think any great record collection is incomplete without a copy. Definitely …

Super Session is an album from 1968 by Al Kooper that also features guitarists Mike Bloomfield and Stephen Stills, although Bloomfield and Stills do not play together on the album. Side one contains tracks featuring Kooper and Bloomfield and side two Kooper and Stills. The record peaked at number 12 on the Billboard 200, and has been certified a gold record by the RIAA.

Kooper and Bloomfield had worked together previously on Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited and backed him at his controversial appearance at the Newport Folk Festival in July, 1965. Kooper had recently left Blood, Sweat & Tears - a band he formed - after their debut album was recorded and became an A&R man for Columbia Records. Bloomfield was a member of Electric Flag (which also featured keyboardist Barry Goldberg, drummer Buddy Miles and bassist Harvey Brooks), but that group was imploding. Kooper invited Bloomfield to a studio jam session, and when Bloomfield agreed Kooper booked two days of studio time and recruited Electric Flag members Goldberg and Brooks to sit in.

On the first day, the quintet recorded a group of mostly blues-based instrumental tracks, including His Holy Modal Majesty, a tribute to the late John Coltrane. On the second day, Bloomfield failed to show up. That's when Kooper called Stephen Stills, who was then in the process of leaving Buffalo Springfield, to fill in. With Stills now playing guitar, the musicians cut several mostly vocal tracks, including It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry (from Highway 61) and a lengthy and atmospheric take of the Donovan song, Season of the Witch.

The resulting record - this one - cost just $13,000 to make and went gold upon release. It's success opened the door for so-called "supergroups" (Blind Faith, Crosby, Stills & Nash, etc). Kooper eventually forgave Bloomfield for his disappearing act and the two later played in concert together on several occasions, which resulted in the album The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper, a sort of Super Session follow-up.

The copy I am listening to is the Mobile Fidelity reissue, released in 1983, which sounds exceptional. A nice punchy low end, full midrange and highs that aren't too bright. The vinyl is a little noisy, but that's probably because it's a previously owned record. It's not terribly noisy, it's just not as quiet as most of the other records in my collection. Over all it sounds great. It is somewhat hard to come by but can still be found in decent shape for about $100. I've seen a few here and there priced even less, and several priced quite a bit more.

Aside from the stereo version, a 4-channel quadraphonic version was also released, although I never understood why. I never got into the whole quad thing when it happened, which was a fore-runner of today's 5:1 or 7:1 surround sound.

A limited edition hybrid SACD by Audio Fidelity was also released in September 2014.

Session photos

The really interesting and odd thing about Super Session is it's success. Kooper said in an interview with Bloomfield Notes several years ago, “That was the last thing on our minds, that it was going to be a successful record. I was trying to emulate the Blue Note jazz records of the ’50s in concept, put a bunch of guys that can really play in a room and let ’em jam. Make rock ’n’ roll more of an art form, comparing it to those jazz records. And it turned out to be the most successful record of our careers.”

The timing was, in a word, perfect. All three key players were at career forks in the road. But it was probably, on some cosmic level, always meant to happen. Kooper and Bloomfield, having met at Bob Dylan's Like A Rolling Stone studio session in 1965, hit it off when Kooper saw what Bloomfield could do with his guitar. When keyboardist Paul Griffin moved from the Hammond B-3 organ to the piano, Kooper - who'd never played a B-3 before - began improvising on it. Dylan liked what he heard and told him to continue playing. As Kooper later told it, “there is no music to read. The song is over five minutes long. The band is so loud that I can’t even hear the organ, and I’m not familiar with the instrument to begin with. But the tape is going, and that is Bob fucking Dylan over there singing, so this had better be me sitting here playing something.”

Kooper’s keyboard and Bloomfield’s guitar became the song's unlikely signature sound, and Dylan was so impressed he invited both men back to the studio for the sessions that would result in Highway 61 Revisited.

In 1966, when Bloomfield was riding high with the Butterfield Blues Band and their iconic East-West album, Kooper was experiencing similar success with the Blues Project. But by 1967 they had both left those bands. Kooper went solo and Bloomfield formed Electric Flag. A few months after the Monterrey Pop Festival, where both musicians appeared separately, Kooper formed Blood, Sweat and Tears and began work on their debut album. But by the following spring both Kooper and Bloomfield were again out of work and that’s when Kooper - who’d begun serving as an A&R man for the Columbia Records (who had signed him as a solo act) - got the idea for this record and called Bloomfield.

“It was really a fated thing,” Kooper told writer Jeff Tamarkin in an interview in the 1990s. “We had so much in common that we had to do something together. So many similarities. We had both played on the Dylan sessions and we were friends through the Butterfield and Flag period. We were both approximately the same age, we were both Jewish, we both loved blues, we both were in blues bands that we left to form horn bands. We were both thrown out of the horn bands that we formed and then there we were. There was a real genuine affection for each other. So when I started working as an A&R man at CBS, I called him and said, ‘Let’s make a jam session album,’ and he was into it.”

But after one day in the studio Bloomfield, who suffered from insomnia, disappeared. “Bloomfield split in the middle of the night,” Kooper told Tamarkin. “He left a note that said, ‘Couldn’t sleep, bye.’ So I called every guitar player I knew in Los Angeles and San Francisco - Jerry Garcia, Randy California, Steve Stills and I don’t even remember who else. Stills was the one who got it together.” They worked blind, as nobody had any new material on offer. Also, Kooper was worried about getting the rights for Bloomfield - who was then signed to Atlantic Records - to appear on a recording for another label, a not so insignificant detail that needed to be worked out. But the way it happened is how Atlantic ended up with Graham Nash - who was at the time signed to Epic with the Hollies - to round out their new group, which at that moment in time consisted of David Crosby and Stephen Stills. The labels simply swapped Stills for Super Session and Nash for what would become Crosby, Stills & Nash.

Talk about fate. Only at that moment in time, and what if it hadn't worked out?

Super Session was and still is a groundbreaking record, the first real rock jam session to get an official release. It was an unplanned magical moment, the kind of creation that will likely never happen again in this modern world of pre-packaged, committee-made music. Kooper is now more-or-less retired at 76, and among his many achievements over the ensuing years was his discovery and nurturing of a fledgling Florida band called Lynyrd Skynyrd.

Bloomfield died in 1981 under mysterious circumstances at age 37.

UPDATE:

I have now acquired the Speakers' Corner edition of this record. The hype sticker on the front cover proclaims that "this LP is an entirely analogue production!" and because there's an exclamation mark at the end of it I'm willing to gamble and take their word for it.

But it's not much of a gamble. Speakers' Corner is a label I have come to trust. I have many of their releases in my collection and every one of them sounds excellent. They are a dedicated bunch of music lovers and this record was pressed at Pallas, In Germany, who are renowned for quality pressings.

This pressing sounds wonderful! The stereo separation is obvious, maybe a little more pronounced than on the MoFi pressing (but not much), and the centre sweet spot is right where it should be. Of course, this being a brand new Speakers' Corner pressing means it's a very quiet record - a bit quieter than my second hand MoFi - and it's obviously an analogue production. That is something I really do hear, and it's missing on every one of the digital versions of this recording I've heard. Spaciousness and warmth - the two hallowed ghosts of analogue. Some believe, some don't. But on a half decent rig it is very much audible.

So. Which pressing is the better one? At this level it just doesn't matter. When I listen to either one I am delighted by how spectacular they both sound. There's nothing wrong with either one, although I suppose there may be some slight differences. Is the MoFi a bit muddier? Maybe, but so what? It still sounds fucking great. We're talking pure analogue here, so it's hard to find fault, and any faults could be related to your turntable, speakers, amp, cables or even the electrical system in your home. Or maybe it's your ears. So just listen to the music and enjoy it.

I think I'll probably trade the MoFi and use the equity to get some more really good records into the collection!

This is one of my all-time favourite recordings - either pressing will do - and I think any great record collection is incomplete without a copy. Definitely …